Chapters - Quick Access:

Petra before the Nabataeans

Evidence of early settlements since the Paleolithic Age

Arrival and rise of the Nabataeans

The Nabataeans in the territory of Edom, sources of wealth, the Greeks loot "Petra", powerful neighbors

Petra / Raqmu becomes capital

Early traces of settlement and documented references, Petra becomes station of the Incense Road, oldest monumental tombs

Beginning of the 1st century to 30 BC

Greatest expansion of the Nabataean Kingdom, its dependence on Rome, conflicts with Herod and Cleopatra, end of the Ptolemies

Last decades 1st century BC

Obodas II and Syllaeus, Nabataeans strengthen economically, early facade tombs, preparatory work for monumental construction

The heyday of Petra, 1st century AD

The building activity in Petra and the Nabataean Kingdom until its end in 106 AD

Roman province, 2nd and 3rd century

Mysterious annexation, Petra remains the metropolis of the new province, new building boom, gradual decline

Byzantine period to Middle Ages

Christianization, great earthquake 363 in Petra, church buildings, crisis and end of the city, Islamization, Crusaders in Petra

Rediscovery, modern times, present

First European visitors in Petra, beginning of systematic exploration, UNESCO World Heritage Site, new museum

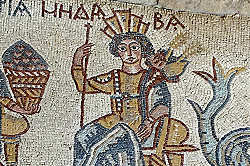

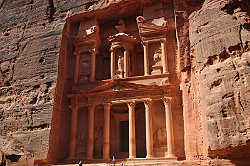

Two sets of five steps over a cavetto (concave moulding) cornice, and fascia (horizontal mouldings). A non-decorative attic above the classical entablature, supported by the pilasters. "Hegra" refers to the second largest Nabataean settlement on the southern border of the kingdom, today's Mada'in Salih in Saudi Arabia.

Two sets of five steps over a cavetto (concave moulding) cornice, and fascia (horizontal mouldings). A non-decorative attic above the classical entablature, supported by the pilasters. "Hegra" refers to the second largest Nabataean settlement on the southern border of the kingdom, today's Mada'in Salih in Saudi Arabia.