The Blue Figure, 2017

How do we see refugees? The refugee has become a multifaceted symbol, the most prominent political figure of our time. Not just because it is so claimed by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNWRA), and other relevant humanitarian organizations, but because of the reality of the refugee's existence throughout the world.

- auch interessant in UiU -

Amidst all this, the migrating human being stands as an abstract symbol, not only within the UNHCR logo, but in reality as well. An abstract symbol of a blue figure without a specific national, religious, ethnic, or gender identity. Since the moment of inception as a representation, the refugee is depicted as a victim, a symbol for the tragedy of exile.

In this interpretive project, an attempt is made at deciphering this blue figure, removing it from the custody of its logo, and liberating it not only from its vulnerability and loneliness, but also placing it in other contexts. Taking the blue figure out of its logo brings back its humanity. Freed, the figure is turned from being a symbol or icon to a normal human being, thus revealing new horizons. We are all refugees until proven otherwise.

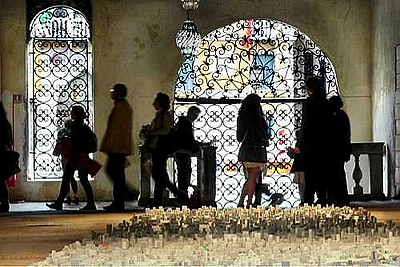

No Refuge, 2017

Without commenting on the act or motives behind the assassination of the Russian ambassador in Ankara, the fact that the incident occurred at a gallery - a cultural space presumably safe and neutral -- cannot be overlooked. In an unpredictable moment, the "white cube" was inadvertently transformed into a stage for fear and anxiety.

The sounds of gunfire, the words "God is great" and "Aleppo", and the frantic gesturing of the perpetrator turned the scene from a typical exhibition opening to a spectacle reminiscent of performance art, which culminated in the now iconic image of the ambassador's lifeless body.

Historically, art always had an intimate relationship with politics, and here was an instance of art being at the centre of events -- not as an allegory, but as a real political episode.

Confronted with this violence that has engulfed the world, this installation asks questions like: Can exhibition spaces still be considered sanctuaries for cultural activity? Where are aesthetics found in such strenuous circumstances? Are there still any boundaries between the actual and the imaginary? And, can art exist without an artist, as the mere theatre of reality?

The Flag, 2013

At the time of the first Intifada, and perhaps even before that time, possessing the Palestinian flag was prohibited and considered a crime punishable under the laws of the Israeli occupation. The flag would be covertly made inside the home, from rags and leftover pieces of fabric: an old dress, pillowcases, traditional costumes, a pair of father's pyjamas, anything that could be cut with scissors and handsewn with a needle and thread. The flag would emerge out of any available fabrics, even if the colours were not solid and contained flowers, stripes, or patterns. A flag that was sewn rapidly and hung publicly to celebrate the life of its independent, secret and forbidden state, before soldiers waged a bitter war to bring it down and confiscate it, disturbing the calm atmosphere and the joy of the land. (This is just one of the many stories of the flag to be told).

The Zebra Copy Card, 2009

Highlighting the surreal and adaptive strategies of Palestinians in straitened circumstances, The Zebra Copy Card springs from the larger story of a Gaza zoo that found itself without any exotic displays. Nadal Barghouti, son of the zoo owner, hit upon the solution of transforming two white donkeys into zebras using masking tape and hair dye. The results were an enormous success, but the incident says something more about the transformative capacity of imagination. Hourani’s painting lightly pushes this further, enquiring into the potential for art to deceive, delight and confuse us with its powers of representation.

Picasso in Palestine, 2009-2011

The project Picasso in Palestine was developed over the course of two years. In a collective effort to bring a unique painting of Pablo Picasso (Buste de Femme, 1943) from the collection of the Van Abbemuseum in the Netherlands to Palestine, the project illustrates the difficulties that surround the exchange of artworks between nations, museums, and artists. It laid bare the numerous regulations and infrastructures that make up an international art world. Where many believe it is a political project by nature, Hourani has always declared it not to be directly political, instead offering insights on the conditions of exchange it had shown.

Shown in the exhibition are various interpretations of the Buste de Femme on display in the International Art Academy during the summer of 2011, as well as video documentation. Perhaps most telling is the focus on the guards, who made this possible as much as Hourani himself, again disengaging himself from the direct relation, into a common understanding of how one can work or be as an artist or curator.

The large photograph was taken at Darat al Funun in 2016, as part of Hourani’s instruction for “do it بالعربي”, Rotation... of Picasso in Palestine, 2015. Using the photograph of the Buste de Femme on display guarded by two guards, he adds layer upon layer by instructing two new guards to stand guard over the exhibited photo, a photograph of which is in turn displayed at the next venue, with new guards, and so on. With every venue, the original Picasso fades further into the background.

© Text und Bilder: Courtesy Khaled Hourani und Darat al Funun.

Khaled Hourani

Die Retrospektive in Darat al Funun wurde von Februar bis April 2017 gezeigt.

Sie fand im Rahmen des Programms "Falastin al Hadara" statt, das Wegbereiter und Vertreter der aktuellen Szene der Kunst Palästinas präsentierte.