Since this exhibition is the consequence of a deliberate and tireless effort to inaugurate it at the 49th Venice Biennale, questions may arise as to its location and strategy, especially in light of the considerable expense and bureaucracy involved. Why Venice? Why exhibitions? The answers to these questions are complex and multi-layered, and range from straightforward, logistical facts of statistics and visibility vis-a-vis the biennale’s continued significance in contemporary art, to much deeper issues of history and the realities of contemporary culture relations.

The African presence in the Venice Biennale has always been minimal and at best sporadic. Since its inception only one African country, Egypt, has maintained a national pavilion, yet the fact that Egypt was one of the earliest non-European nations to establish a pavilion beginning with the 2nd Biennale indicates that there is a long-standing awareness of the biennale’s significance as an international cultural forum. For a brief period South Africa presented its artists in Venice before it was ostracized for its racial laws. Otherwise throughout its history, only two traveling exhibitions of African art made it to the Venice Biennale ̶ one in the 45th Biennale and the other in the 46th Biennale. Both exhibitions were organized by Western curators, and were in many ways marginal to the main events of the Biennale although the Africans won the first exhibitors’ medal at the 45th Biennale. It is equally noteworthy that as recently as the 48th Biennale, of over 107 artists invited to d'APERTutto, the main exhibition organized by artistic director Harald Szeemann, only three were African. On a certain level therefore, this exhibition is part of an effort to remedy the virtual absence of Africa in the Venice Biennale, and hopefully in other significant international cultural forums of its kind.

Some may wonder why such forums, and exhibitions in general are so important as opposed to texts or other means of presenting African art? One may put the answer rather simplistically:

If You Do Not Exhibit, You I Do Not Exist!

Exhibitions remain exemplar of how art history is produced.They are the building blocks of art history and therefore crucial in moving art from the private to the public domain. In the cultural politics of the past two centuries, exhibitions and the curatorial practices behind them constitute the most enduring and perhaps most powerful means of selecting, staging, and ultimately canonizing art. As Walter Grasskamp has observed: [H]istoriography, including art historiography, is only possible if a few events are selected from the chaos and peddled. Historiography pretends to go by the worth of events, as contemporaries supposedly saw it, but uses its own evaluation. 1

Exhibitions and forums for showcasing artistic creativity are part of art history’s strategy to transform this ‘chaos' — to use Grasskamp’s term — into more manageable units, out of which it creates the semblance of a coherent historical narrative. Needless to say that this strategy involves not only art historians and critics, but an entire culture machine comprised of an array of cultural managers and brokers including curators, patrons, museums, art galleries, art dealers, agents, and collectors. As one of the most well attended showcases of contemporary art the Venice Biennale provides this increasingly global machine with a ready-made package of what is considered the latest trends on the international art scene. Curators, museum directors and gallery owners, art critics and other specialists from virtually every corner of the planet descend on Venice for a glimpse of this official currency, with undoubtedly significant consequences for artists and cultural constituencies with any interest in the global contemporary art scene. Given this fact, it becomes particularly interesting that African artists are absent, for, while the paucity of African national pavilions in Venice may be explained by economic reasons or the lack of consistent national policies that prioritize culture, these reasons do not explain the absence of African artists from the invitational exhibition at the Biennale for which the artistic director is responsible. The later, it seems to us, speaks to reluctance, even unwillingness on the part of curators to acknowledge these artists and their provenance as part of contemporary art and our moment in history.

Whereas in a distant past, it could be argued that little of known in the West about these artists, such excuse no holds since many of them work now internationally alongside their contemporaries from elsewhere, producing work that speak to issues quite analogous to those that currently preoccupy other artists. It is difficult to name or qualify this unwillingness, yet it fits into a pattern that appears to change very little even as these artists become more visible on the international scene and new bodies of knowledge are generated around their practice.The 1997 Venice Biennale, along with the last Documenta, provide striking illustrations of this fact. The director of the 1997 Venice Biennale, Germano Celant, may not have voiced the same illogic upon which his predecessor, French curator Jean Clair, excluded African artists from the main exhibition, but his actions did not evince a different conviction. Not a single African artist was included in the Biennale's main exhibition, which Celant organized as a survey of contemporary art in the late 20th century under the banner 'Future, Present, Past.' Effectively, the curator’s position was that African artists have no place in any narratives of contemporary art in the late 20th century, despite their presence and the fact of their contributions to contemporary culture even in the West. Almost a decade earlier, a much less knowledgeable British art journalist named Brian Sewell had written that non-Western artists did not deserve any more than a footnote in the history of modern art in the 20th century. At the end of the century Celant’s position seemed to echo Sewell’s. And this is not peculiar to the Venice Blennale. The story of the last Documenta X of Kassel, which is widely acknowledged as perhaps next only to the Venice Biennale as a showcase of significant contemporary art production. Although Catherine David, the director of the Documenta X made last minute efforts to invite African artists, their presence was nonetheless almost nonexistent and came across quite clearly as an afterthought in an exhibition supposedly devoted to issues of globalization and internationalism in the visual arts. This was made even more graphic against the backdrop of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale in South Africa where Okwui Enwezor, its artistic director and his team of international curators presented an inclusive, comprehensive narrative of contemporary art with sufficient evidence of the presence and strength of African artists as part of a global contemporary culture. Judging by the level of disparity between the two aforementioned exhibitions, it was clear that the absence of African artists in international spaces and exhibitions is not as a result of any shortcoming in their work or practice, or lack of knowledge of their existence, but rather points to a persistent shortcoming in the political will of culture brokers and managers in the West to locate them alongside artists from other parts of the world.

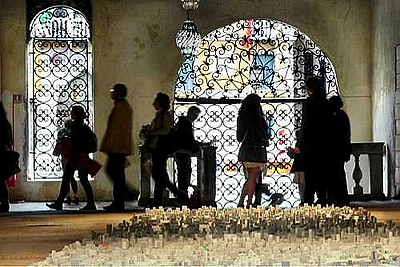

It is against this background that Authentic/Ex-Centric is presented at the 49th Venice Biennale, as the first exhibition of its kind conceived and organized by African curators. It is both an intervention in the patterns of narration of contemporary culture, a re-insertion of passages otherwise likely to be left out, as well as an effort to assume responsibility in telling one’s own story.This is not to privilege any argument that only Africans are capable of presenting their own story. It simply rests on the clear understanding that in order to form a clear perspective of Africa's place in contemporary culture, a level of self-definition and self-representation is required, and even more so when others are unwilling to take that reality as a given.Towards this end, the exhibition is presented as part of a series of like projects under the auspices of The Forum for African Arts, an organization formed by African and other concerned curators, art critics, artists, and scholars with the aim to promote and document contemporary African art. At present The Forum includes among its members: El Anatsui, Ghanaian artist and professor at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka; Ibrahim El Salahi, Sudanese artist; Koyo Kouoh, independent art consultant and cultural activist, Goree Institute, Senegal; Marilyn Martin, Director of the South African National Gallery; Tumelo Mosaka, South African curator; Florence Alexis, Director of Visual Arts, Afrique en Creations in Paris; Obiora Udechukwu, Nigerian artist and distinguished professor at St. Lawrence University, Canton; Okwui Enwezor, Nigerian art critic, curator and Director of Documenta XI; Gilane Tawadros, Director of the Institute for International Visual Art, London; as well as the present authors. It is the wish of The Forum to support and propagate the work of African artists and produce the knowledge to ensure that they take their deserved place within the spaces and narratives of international contemporary art.

Salah M.Hassan and Olu Oguibe

June 2001

Excerpt from the essay published as Preface in the book: Authentic / Ex-centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art

Note

1. See 'For Example Documenta, or How Art History Is Produced?' In Reesa Greenberg et al (eds.). Thinking About Exhibitions. New York: Routledge, 1996, p. 68.